Teacher For Learning

Teacher for Learning

Organize Knowledge

The way we present information and how we subsequently categorize new knowledge can make dramatic differences in our students’ learning. We can help learners to make sense of new information by being explicit about how we suggest information fits with prior knowledge.

Play this game that shows how organization matters

(Modified from: Fink, D. (2015) Creating Significant Learning Experiences. STLHE, Vancouver.)

- Count all the vowels on the next page.

- Dollar bill

- Dice

- Tricycle

- Four-Leaf Clover

- Hand

- Six-Pack

- Seven-Up

- Octopus

- Cat Lives

- Bowling Pins

- Football Team

- Dozen Eggs

- Unlucky Friday

- Valentine’s Day

- Quarter Hour

- How many vowels did you count?

- How many words do you remember?

This activity often generates a lot of groans. Participants want to succeed so much in the task assigned the first time that they barely pay any attention to the words themselves. When they are asked to shift and remember words, they are frustrated because they feel misled.

- Now look at the words again.

Did you notice the pattern of organization: that each word is associated with a number?

- Try the game again.

How many words did you remember this time?

Most people remember more words the second time that they play the game. There are three reasons for this. First, they knew what the real task was by being provided the criteria for success. Second, the information was organized in a way to aid memory. Third, they were given more than one opportunity to practice remembering to stimulatethe recall of previously acquired information. This simple game covers a great deal of the seven evidence-based principles for learning that are discussed in this module.

Strategies for organizing information

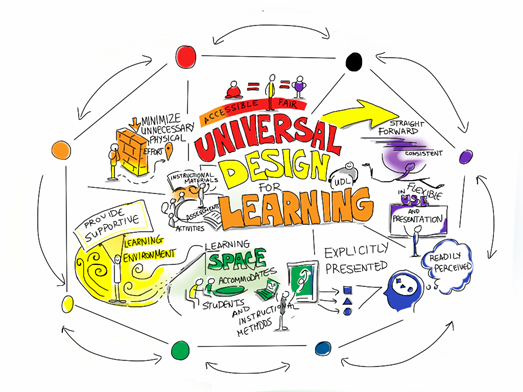

Consider Universal Design for Learning

Universal Design for Learning acknowledges that there is great variation in how individuals learn. Two major points of Universal Design for Learning:

- Learning should be designed to be accessible to everyone

- Information should be conveyed in a variety of ways, known as “multiple means of representation.” For example, instead of using just a wall of text, consider adding some visual elements. If you do add an image you should explain it using the description tag available online. Sometimes a video is the best way to explain something, but if you use video, be sure to always include transcripts and captioning. (The information about Universal Design for Learning goes into great depth about this).

Mind mapping

Mind mapping has been found to be an effective means of helping students organize new learning while reinforcing previous learning and improving information retrieval. Some studies have found that using mind mapping as a learning strategy facilitates memory and critical thinking.

If you are still not convinced, check out The Theory Underlying Concept Maps and How to Construct and Use Them.

Keep in mind that mind maps are not just good for students, they are great for teachers too. When planning your course, you could use a mind map to decide what content to include and how they are connected. You could then share it with your students so they can get an overview of how you see your course fitting together. Using mind maps to outline your course syllabus not only models how to organize information but also adheres to the universal design principles of conveying information in multiple modes, according to Biktimirov & Nilson, 2006 in Show Them the Money: Using Mind Mapping in the Introductory Finance Course.

Extend Activity

Using MindMup or another visual organizer tool in the Extend Toolkit, create a concept map of your course syllabus.

Please upload or link your concept map as a response to the Syllabus Concept Map activity.

As evidence of completion, please plan to enter the web address for your response in the Teacher for Learning badge submission form.

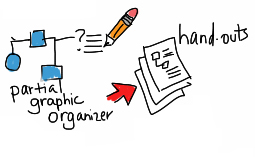

Offer a partial graphic organizer

Instead of providing your complete lecture notes on the LMS, consider offering a partial graphic organizer (see Visual Organizer Tools in the Extend Toolkit) that highlights some of the key learning. This creates high impact learning as students are able to actively participate in their learning, especially if you prompt them to record in important facts to create the full picture. This practice should also help to ensure attendance remains high. In Increasing Text Comprehension and Graphic Note Taking Using a Partial Graphic Organizer, Robinson et al (2006) describes how using partial graphic organizers can aid in learning.

- Split your page so that it looks like Cornell notes.

- Take notes that make sense to you in the right-hand (two-thirds) space.

- When you are done, use two different colour markers to highlight key points and new or specialized vocabulary. Use the left-hand (one-third) space to rewrite those key points and vocabulary with explanatory text.

Download a PDF version of these Cornell Notes.

Allow time to process

If we want our students to succeed it is ideal to model successful behaviours that have been shown to be beneficial to learning.

It is widely known that students who take the time to review their notes do much better than students who do not. With that in mind, use the last 10 minutes of your lecture time to allow students to process what was just covered. Doing so has two main benefits: it encourages you to think about the main learning you hope to cover during your lecture, and it allows students to immediately retrieve, use, discuss, and question what they have just learned. Invariably, they can also discard confidently held misinformation in doing this.

You can follow this pattern to organize the 10-minute processing time, allowing about two minutes for each step:

- Ask your students what they think would be a good exam question based on the lecture they just heard.

- Ask your students to flip their page over and draw a picture that represents a key idea related to this “good exam question.”

- Have your students turn to a neighbour and share their Cornell notes.

- Ask them to compare their proposed exam questions and drawings. Can they answer each other’s questions? Do the drawings make sense to each other?

- Finally, and possibly most importantly, ask the students what questions remain.

You will find that structuring the end of your lecture in this way is more effective than simply asking the students, “Do you have any questions?” Students often interpret that question as a signal that it is time to pack up their laptops and belongings. In contrast, the summarizing time and activities makes the students’ thinking visible and provides an immediate opportunity for students to confront any misconceptions.

Extend Community

Do you have any successful tips/techniques/best practices to share with regard to how you typically end your lectures? Or if you do not teach, perhaps successful ways to end a presentation?

Visit the Extend Community Space Lecture/Presentation Endings discussion area (in the #teacher4learning channel) to share your thoughts!

Extend Activity

Watch a TED Talk or conference keynote video to practice your own note taking skills using Cornell Notes.

Please upload or link to your Cornell Notes, include the name and link for the video you watched, and describe your experience note-taking as a response to the Cornell Notes activity.

As evidence of completion, please plan to enter the web address for your response in the Teacher for Learning badge submission form.